Continuing with our theme of the 1900 Paris Olympics, today on Olympic Mysteries we are looking into another case muddled by uncertainty, that of French fencer Viscount de Lastic. One might assume that if anyone from the 1900 Games were to be remembered, it would be a member of the nobility. Unfortunately, at the time, the Olympics had yet to distinguish itself from other international sporting tournaments and, with the Paris Games further diluted in importance by being mixed into that year’s World Fair, many may not have even been aware that they were participating in the Olympics, let alone have found it prestigious enough to be worth special mention. If this were the case for the average sportsman, then certainly it would be more so for a member of the nobility whose life would have revolved around many uncommon exploits, and for whom participation in the first round of a fencing tournament may not have been of particular note.

What we know for certain is that a man holding the title of Viscount de Lastic took part in the individual épée competition at the Paris Games and was eliminated in round one of the event. He was neither the only member of the nobility taking part nor was he the highest-ranked. Gabriel, Count de la Falaise, for example, finished fourth in this event and won the sabre tournament.

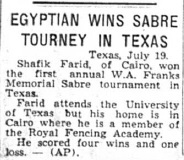

(The Coat of Arms for the de Lastic family)

The de Lastic family has been around since at least the 11th century, leaving many potential branches to explore. We suspect, however, that Viscount de Lastic was actually Hubert Jehan de Lastic Saint Jal, but we are unable to confirm it. He was born January 15, 1874 and died June 1, 1965 at the age of 91, which would have at one time, appropriately enough, made him among the Oldest Olympians.

(Biography from Des hommes et des activités autour d’un demi-siècle, page 428)

According to one biography, this de Lastic was a cavalry officer and a sports patron, both of which would align well with an interest and competitive history in fencing. He was decommissioned in 1908, but called back to serve with the 10th Hussards during World War I. After that, he seems to have spent much of his time active in various sports administration roles in France.

There is nothing to suggest, therefore, that Hubert Jehan de Lastic Saint Jal was not the Olympic fencer but, unfortunately, there is nothing to confirm it either. Given his extensive sports patronage and decorated military career, there would seem to be little reason in any biography to mention his single-round participation in a fencing tournament nestled within the 1900 World Fair. Although by 1965 participation in the Olympics would certainly be worthy of note, if there is an obituary that mentioned this fact, we have not seen it. Thus, despite all of the supporting evidence, the case of Viscount de Lastic must remain among our Olympic mysteries.