And so Switzerland’s electorate has voted not to pursue the 2026 Winter Olympics for the city of Sion. This occurred shortly before the U.S. Open golf championship was held at Shinnecock Hills on Long Island, and a few weeks before The Open Championship of 2018 will be held at Carnoustie Golf Links in Angus, Scotland. And Wimbledon starts today, with those big Rolex watches at the ends of the main courts, which would never be allowed at the Olympics. What could these possibly have to do with each other? Read on, my friend, and we shall discuss.

For the past decade the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has watched in what must be anguish as city after city has spurned their chances to host an Olympic Games or Olympic Winter Games, almost certainly concerned at the cost of hosting for their city, while wondering what exactly are the benefits. Sion was only the latest. Boston, Massachusetts was chosen as a potential host city for 2024 only to reject the offer a few months later. Norway, almost the quintessential host of a Winter Olympics in 1994 with Lillehammer, also voted against bidding for the 2022 Winter Olympics. And there were many more, in Germany, in Poland, ad seemingly nauseum.

What should be made of this and what should the IOC do to reverse this trend, with the future of the Olympic Games at risk if adequate cities cannot be found? I think there are a number of things that are possible and some of them relate to the US Open and The Open Championship and how those are conducted. Some of the other thoughts you will read in this post are ideas gleaned from many sources, some would say stolen, though I will give them credit.

The cost of hosting an Olympic Games has risen beyond reason in the last 30 years. Los Angeles hosted the 1984 Olympics for $545.9 million (US)[1] while the cost associated with the 2008 Beijing Olympics is often reported to have been $31 billion. The Opening Ceremony at Beijing is reported to have cost $310 million alone. Hosting an Olympics has become an arms race, with each city trying to outdo the previous host, and usually spending more and more money to do that. Almost all agree that the 2008 Opening Ceremony was the nonpareil Olympic ceremony, but basically it’s a party, and if you give me $310 million, I promise I will throw you one hell of a party, too.

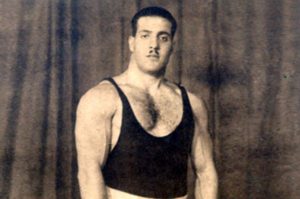

Let us pause to remember a voice of reason in the cost of Olympic Games, yet one who is often forgotten, and during the run-up and the hosting of the 1984 Olympics was often vilified by the IOC and the European press because of frugal, often dogmatic ways. Peter Ueberroth was the chairman of the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee, a Games that ended with a $232.5 million surplus (you cannot call it a profit for US federally recognized non-profit organizations). How did he do it?

First of all, shortly after he was named chairman, Ueberroth went to the Helms Library in Los Angeles (now sited at the LA84 Foundation Library, one of the products of that $232.5 million surplus), and sat down and read all the previous Official Reports to see what previous Games cost, and what the primary source of those costs were. He came to the conclusion that the most important factor in Olympic Games expenses was the building of new stadia, and he vowed that he would host the 1984 Olympics without building new venues.

Ueberroth had an advantage in that Los Angeles has a lot of athletic facilities, but we’ll get to that later. He actually had to build 3 venues – a swim stadium, a velodrome, and a shooting range – but he got McDonald’s to fund the swim stadium and 7-Eleven to fund the velodrome[2], and the shooting range cost was only a rounding error.

What else did Ueberroth do that allowed Los Angeles to arrive at a surplus? In the book on the 1984 Olympics by Kenneth Reich, Making It Happen: Peter Ueberroth and the 1984 Olympics, it is described that when they were deciding on choices and costs, his mantra was, “It should be well done, but not ostentatious.” And it was never ostentatious. It was simple and somewhat austere compared to the Games that would come later, and the IOC thought it was downright cheap, but it worked.

So how can cities and the IOC use this information learned from Peter Ueberroth, a man Dick Pound has described to me as the most important member of the Olympic Movement who never became an IOC Member? Let’s look at The Open Championship and the US Open golf tournament.

The Open Championship (often called the British Open, which the Royal & Ancient hates) is not open to all clubs in the British Isles to host the tournament. It is held on a rota of courses that is predetermined, and currently consists of only 9 courses: St. Andrews, Carnoustie, Royal Birkdale, Muirfield, Turnberry, Royal Lytham & St. Anne’s, Hoylake (Royal Liverpool), Royal St. George’s, and Royal Troon. Royal Portrush in Northern Ireland will host the 2019 Open but it has not hosted since 1951 and is not a part of the normal rota.

The advantage of this is the 9 host courses on the rota all have hosted the tournament before, usually fairly recently. They know how to do it, they have facilities at the ready, they have committees and committee members available who have previous knowledge of hosting an Open Championship.

Compare this to an Olympic Games in the 21st century. It is given to a city often with no previous experience hosting an Olympic Games, such as Rio de Janeiro, Athens (last hosted in 1906), and the like. They don’t know how to do it, they have never hosted, often they don’t always have the facilities and must violate Ueberroth Rule #1 by building stadia all over the place, and they don’t have the experience in committees and committee members.

So should the IOC go to a fixed number of cities to host the Olympic Games? I think they need to do something like this although it may not be cities. In fact, I think the IOC needs to distribute Games to countries because of the venue problems and begin to think of an organized rota of cities / nations to host Olympic Games.

Now in the 1970s and early 1980s when the IOC was broke, before Ueberroth made an Olympics profitable (excuse me, surplusable), and before Juan Antonio Samaranch and Dick Pound started the TOP Program, with the help of Patrick Nally and Michael Payne[3], it was always discussed that the IOC should hold all Olympic Games at one fixed site, with Olympia, Greece always quoted as the site of the Summer Games. Fortunately that talk is over now, as that will never work, certainly not in Olympia, as they have no facilities except those left over from the Ancient Olympics, they have no airport, the bus ride to Olympia takes about 6 hours from Athens, and, well, the Greeks are broke, some of which is still blamed on the 2004 Olympics.

But the IOC could go to a rota of cities and nations. Perhaps consider 3 sites in Europe, 2 sites in North America, 2 sites in Asia, and 2 open sites to rotate between South America, Africa, and Oceania, so that NOCs and IFs would know decades in advance where the Games would be held. It does not always have to be the same site in Europe or North America or Asia, although that would help if cities were to step up. I don’t really care how many cities / nations in the rota or where they are, but I do think the IOC should insist that only cities that already have Olympic facilities available should be allowed in the rota.

The advantages of this idea are that only cities which have the available facilities and don’t require major building projects to host an Olympics will be chosen – see Los Angeles. It also eliminates the now exorbitant cost of bidding for the Games, and often losing the bid. Like the courses that host Open Championships, the cities will also have the experience of hosting a Games, with facilities, infrastructure, and committees and committee members available. Look at Los Angeles, which called on the sporting structure that was formed in the aftermath of the 1984 Olympics, the LA84 Foundation, which was a big part of why their bid for 2024 / 2028 was so solid.

The IOC will not like the rota idea but I think it has to go to something like this. They always say they want to spread the Games to all nations of the world, but that is an idea from the 19th century when the Games had 9 sports, 12 nations, and about 250 competitors (1896 Athens). The Summer Games now have 34 sports, 206 nations, about 11,000 competitors, and even a larger contingent of media of all types. They are now so large that the IOC has to recognize that only a few cities in the world, and only a few nations in the world, can host a modern Olympic Games.

But you will say, “Look, the Games will only return to a city every 32-40 years or so. The personnel experience will be gone by then. That’s no advantage.” And I now give you the US Golf Association (USGA) and how they host US Open Championships for the second main part of my argument.

The US Golf Association does not do a formal rota for the US Open, as does the Royal & Ancient, although it returns to certain sites with some frequency, namely Oakmont, Pebble Beach, Shinnecock Hills, Pinehurst, and Winged Foot, among others. But it allows new clubs to host the Open, such as Erin Hills in 2017, and Chambers Bay in 2016 – both considered now marginal choices.

But what the USGA does is they do not give all the responsibility of organizing an Open to the host club and their organizing committee, as the IOC does. Shortly after the club is awarded a US Open (the time before hosting when it is awarded is variable in the case of the US Open), the USGA starts sending their own team to the club. They live there, they work there. They have worked at previous host clubs – they have the experience. And as the tournament gets close, the USGA presence on site increases, since they know how to run the tournament. They take over. Clubs do not always like this, but it’s a necessary evil to avoid the golfing equivalent of Rio de Janeiro.

The IOC does not do this to any degree. They let the host city form their own organizing committee (OCOG) and give them almost full responsibility. More recently, they have acknowledged that OCOGs need help. Until about 20 years ago, the OCOG had to start from scratch, but the IOC has at least started a clearing house of data from previous hosts called the Olympic Games Knowledge Services (OGKS), which can spread information to new OCOGs. It has also formed the Olympic Broadcasting Service (OBS), to assist and take production duties off the OCOGs. But the OCOG in a new host city usually has no experience, effectively, they have no clue. The OCOG reports to the IOC Coordination Commission periodically and tells them how things are going, and the Coordination Commission visits the city periodically to check on progress.

Slightly more than a year prior to Rio, the IOC Coordination Commission realized Rio needed significant help quickly and dispatched Gilbert Felli to Rio on a full-time basis to get things jump started. Fine, but that was too little, too late. The IOC should follow the lead of the USGA and send an IOC team to the host city shortly after it is awarded the Games – 7 years before they are to host the Games. They are the leaders of the Olympic Movement and they need to develop the personnel and the teams that rotate around to the various sites, and use them.

Remember that the US Open and The Open Championships are large sporting events, but nowhere near as large an Olympic Games, and with nowhere near the complexity. I can’t say how many people from the IOC should be living in the host city or for how long, but I do know that 1 person for 1 year is inadequate for the largest sporting event on the planet. Those IOC teams should comprise people in various categories, experts in things like media, finances, sporting facilities, security, international relations, and others.

There are other things cities can do to decrease the costs of Olympic Games. Michael Payne, former director of marketing at the IOC and then at Formula One, recently tweeted that cities should not be allowed to attach the Olympic title to any infrastructure project they elect to do in preparation for the Olympics (https://twitter.com/MichaelRPayne1/status/1006284904248827906). These are projects cities always want to get done – the ring road around Athens in 2004, the upgrade of Hartsfield International Airport in Atlanta in 1996, enlarging the Sea-to-Sky Highway from Vancouver to Whistler in 2010, building a brand new ski resort near Sochi, and many other such projects.

But these are things the cities have usually wanted for themselves for some time, and when they see the Olympics, they find a way to glom these costs onto the Olympic budget. When that happens, Olympic costs can get astronomical. In fact, Dan Doctoroff, former advisor to New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, often said that the NYC and Boston Olympic bids could be used by governments to catalyze infrastructure deals that wouldn’t have otherwise happened.[4]

Not well known is that there are three facets of the costs of hosting an Olympic Games, best described by Holger Preuß in his excellent book The Economics of the Olympic Games: A Comparison of the Games 1972-2008, and have also been described more recently in the paper out of the Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford study by Bent Flyvbjerg, Allison Stewart, and Alexander Budzier: The Oxford Olympics Study 2016: Cost and Cost Overrun at the Games[5]. The three are: 1) operational costs or the costs of running the Olympics for 2 weeks of the Games, and the costs of funding the organizing committee’s work before and after the Games; 2) direct costs, which is what Peter Ueberroth all but eliminated, which is building stadia and other facilities, such as media centers (Main Press Centre and International Broadcast Centre), and Olympic Villages; and 3) indirect costs, which are the city projects described in the previous paragraph and which escalated beyond belief in the case of Sochi 2014, which built a new ski resort at Krasnaya Polyana for the Mountain Cluster of events, and then built a highway connecting Krasnaya Polyana with Sochi (really Adler, where the Games were actually held).

We’ll start with 3) first, which I already mentioned. Cities have to stop using the Olympic Games for self-improvement projects and then blaming the IOC for the cost of those projects. The IOC does hold the trademark to the word Olympic and as Michael Payne said, they should not allow the word to be used connected to any infrastructure not needed specifically to host the Games.

Aha, you say, but what if this infrastructure is needed to host the Games? By going to a rota, and rarely using new cities, this should not be necessary, and any cities / nations that want to get on the rota should not be allowed if they do not have the necessary infrastructure (see Rio / Sochi).

As to 2), do what Peter Ueberroth said, “Don’t build new facilities.” If you don’t have them, don’t bid for the Olympics. If the city doesn’t have the requisite facilities, the IOC should not award the Games to the city or allow it on the rota. Further, the International Federations (IFs) have to share some of the blame here by demanding more and better facilities, and adding to the host cities arms race. As an example, track cycling is held in a velodrome which few cities outside of France or Japan will ever use outside of the Olympics. It will never pay for itself, but the UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale) mandates an indoor, fixed wooden track facility. A temporary artificial track can be used, as it was for Atlanta in 1996. The UCI will not like that, but we’re sorry.

If you do need some facilities, temporary is the key word. The US Olympic Swimming Trials has been held in Omaha, Nebraska for the last few Olympics, and Olympic journalist Alan Abrahamson has raved about their hosting ability. But there is no natatorium there – they use a temporary pool set up for the trials and the same could be done at the Olympic Games. FINA (Fédération Internationale de Natation Amateur) will not like it, and they do not like the events being held outdoors, as at Los Angeles in 1984 and Barcelona in 1992, but both things would greatly decrease the cost of building more stadia.

Temporary facilities can be placed inside already existing structures, such as convention centres, or such centres can be built for the city to use later. Those will make money, and cities love convention centres because they bring business, people, tourists, and money to them for many years. The media centres – Main Press Centre and International Broadcast Centre (IBC) – should be built with future use as a convention centre in mind, or in the case of the IBC, future use as a broadcast centre for the city. As to Olympic Villages, virtually all major cities can use more low-cost housing and these villages, if they need to be built, should be designed with that future need in mind.

Another example of an IF that forces OCOGs hand is the ISU (International Skating Union) which mandates that speed skating must be held on an indoor oval at the Winter Olympics. I love speed skating, but those never (or rarely) get used after the Olympics. Strangely the ISU does not require its World Championships to be held on indoor oval. The IOC needs to tell the IFs that they run the show at the Olympics and we will do what is cost conscious for cities. Currently the IFs tell the cities and the IOC what they are entitled to, but paraphrasing Col. Nathan R. Jessup, “[We] don’t give a damn what you think you are entitled to.”

The cities must be allowed to use temporary facilities at every turn, if they do not have pre-existing stadia for each. Building a hockey (field) stadium is a nice idea perhaps in India or some cities in Europe, but at most cities it will become a white elephant. If the city does not have enough structures, either do not let that city in the rota, or allow them to use temporary structures, ideally structures that could even be rotated to the next city to host, similar to a traveling circus, that brings all its tents with it to each new city.

Further, OCOGs should do as Ueberroth did and get corporations to build facilities, if they need them, and here we look at Wimbledon. I think the IOC should loosen up their rules and allow more advertising at Olympic sites, which is now forbidden. Sorry, but Wimbledon is a very staid, proper event, which is what the IOC wants, yet I don’t think anyone is complaining about that Rolex clock that is seen every time the camera focuses for 34 seconds on Rafael Nadal hitting his first serve, and for which I assure you Rolex pays Wimbledon a significant sum each year. If you tell a corporation that they can have the Coca-Cola Olympic Natatorium or the Intel Olympic Velodrome, and that their name will show up on virtually every TV in every nation in the world for about 3 weeks, I think the money will appear very quickly to get that structure built.

Finally, on 1), if we have a rota of cities / nations, and the IOC assigns teams to each city / nation immediately after hosting, and the IOC runs the Games as a professional organization, and not allow an amateur OCOG to run them, this will certainly greatly decrease operational costs, because the IOC teams will know, and learn more during each Olympiad, where the money should be spent, and where it should not be. This facet of Olympic costs is relatively well-controlled and is not usually responsible for major cost overruns, but certainly a more experienced team in place from the beginning can limit these costs as well.

The Olympic naysayers will say that this all sounds too simplistic and that Olympic costs will always continue to spiral, as the Oxford study showed (noted above). They will also say that I am an Olympic apologist who is blind to the realties of modern Olympic economics.

Yes, I am a big believer in the Olympic Games and the Olympic Movement. I think it serves a real need by bringing the nations of the world together peacefully for 2-3 weeks every few years, and making the people of the world realize and understand that we are far more alike than we are different (see North and South Korea in PyeongChang). But I am far from an Olympic apologist.

The NOlympics Movement people know only one thing about the Olympics – they have cost too much in recent years. Most have never been to an Olympic Games, compared to my 14. Most have never read a book on the Olympics Games, such as Preuß’s book on Olympic Economics. My Olympic library comprises over 1,000 books, most of which I’ve read, and my CV notes that I have written 27 books on the Olympic Games, so the NOlympics people cannot begin to tell me they know more about the Olympics, or Olympic finance, than I do.

I believe the Olympic Games can be brought to fiscal responsibility but it will take some effort, changing some rules, and doing some things the IOC and the IFs will not like. In the past 30 years there have been fiscally responsible Olympic Games, in addition to Los Angeles 1984 – Atlanta 1996, Salt Lake 2002, and Sydney 2000, and Vancouver 2010 all finished either with a small profit or neutral revenues. So it can be done. And here is my summary of what I believe are the steps that should be done to make this happen on a regular basis:

- Set up a rota of Olympic sites that have the necessary facilities so that building venues and stadia are not a huge part of Olympic budgets, and what this mandates is that if you do not already have the facilities you can’t be on the rota.

- After the Games are awarded to the host city, have the IOC run the Organizing Committee on-site with their own team, rather than trusting OCOGs, who have no experience, to do it.

- Insist on infrastructure costs, or local capital projects, be taken out of Olympic accounting. If the city wants to build it, they can, but it should never be an Olympic cost. If we follow 1., hopefully these projects will not be needed to host the Olympics. If the IOC team is on-site running the OCOG, they should be able to see that this does not get added to their budget.

- The IOC needs to be in charge of how the events are held, and not the IFs, who always want the newest and best facilities, and contribute to the Olympic host city arms race that greatly increases budgets.

- Loosen up the IOC advertising rules by allowing corporations to advertise on site, which will immediately increase the possibility that such corporations will pay for the building of any facilities that are needed.

- Always use temporary stadia and facilities, if needed, and if they cannot be built and paid for by corporations, and always consider rotating these around to future Olympic sites.

___________________

With thanx to David Fay, former executive director of the US Golf Association; Ben Fischer, writer at Sports Business Daily; Hilary Evans (@OlympicStatman); and Rich Perelman, former media director of the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee (LAOOC) and current publisher of The Sports Examiner. All four read pre-prints of this and made suggestions, many of which were included. All mistakes are mine.

Original version had an error that has been corrected and was spotted by Alan Abrahamson. It was Gilbert Felli, not Christophe Dubi, who spent a year in Rio on the IOC’s behalf.

___________________

[1] All financial figures throughout will be in US dollars, not corrected for inflation. Similarly all financial figures for Olympic costs and profits/surpluses should be regarded as estimates. All such financial figures have been sourced from either Official Reports, Holger Preuß’s book on the economics of the Olympic Games (see later in article), or in the case of 1984 Los Angeles, direct information from Rich Perelman, who had a lead role in the LAOOC.

[2] Technically, McDonald’s and 7-Eleven were only sponsors, but all their sponsorships dollars were directed to the swim stadium and the velodrome, respectively, and they did receive naming rights (which could only be used after the Olympics). Information from Rich Perelman.

[3] Rich Perelman points out that even the TOP Program was strongly based on the LAOOC sponsorship program, designed by Ueberroth and Joel Rubinstein, who he notes does not get enough credit for his work on all this.

[4] Info kindly provided to me by Ben Fischer at Sports Business Daily – see https://www.google.com/search?q=Dan+Doctoroff+use+the+olympics&rlz=1C5CHFA_enUS703US703&oq=Dan+Doctoroff+use+the+olympics+&aqs=chrome..69i57.4375j0j9&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

[5] Can be found at this link – https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2804554.