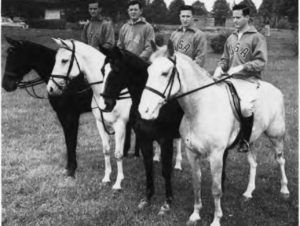

Norman Brinker never competed in the Olympic Games. However, he was on the US Olympic team in 1952 in show jumping, but only served as an alternate and never saw competition. It was only a prelude to an amazing life, whose tentacles within his families would reach multiple aspects of American life.

Brinker made the 1952 US Olympic team while a seaman in the US Navy, stationed in San Diego, where he also attended San Diego State University. A good athlete, he did compete at the 1954 World Modern Pentathlon Championships in Budapest. While Brinker was studying at San Diego State, he met a young tennis player named Maureen Connolly.

Maureen Connolly, often called “Little Mo”, is not well-remembered by today’s sports fans, or even tennis fans, yet she is one of the greatest female tennis players of all time. Little Mo won the US Open Championship, then called the US Championships, at the end of 1951, when she was only 16-years-old. She would retire in late summer 1954, before the US Championships, having won 9 consecutive Grand Slam tournaments that she played in, including the calender-year Grand Slam in 1953, the first woman to achieve that. In that Grand Slam, she lost 1 set. After her 1951 US Championship, there is no record that she was ever beaten again in a match.

Maureen Connolly retired before she turned 20-years-old. She had won Wimbledon and the US Championships in 1952, the Grand Slam in 1953, and the French and Wimbledon Championships in 1954 – she did not play the Australian that year. In late July 1954, she was riding a horse that threw her and broke her leg, sustaining an open fracture. She never played tennis competitively again, officially retiring in February 1955, when her leg had not healed well.

A few months after the accident, June 1955, Maureen Connolly and Norman Brinker married. They would have two daughters together, Cindy and Brenda.

Norman Brinker’s career was not overshadowed by his wife’s tennis feats. He helped start several restaurant chains, including Jack-in-the-Box, Chili’s, Bennigan’s, and Steak and Ale. His company, Brinker International, would later oversee all those restaurant chains, and also Burger King and Häagen-Dazs. Brinker is considered the father of the popular modern casual dining concept. He is also considered to have either invented, or at least, popularized the salad bar, that is now so ubiquitous in many restaurants.

Brinker and Little Mo were together for only 14 years, unfortunately. In 1966 Little Mo was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and she died in June 1969, at only 34-years-old. A fleeting meteor in the sports world, who flamed out early, she also lost her life early, both times from instances beyond her control. Her story was told in a made-for-TV movie in the 1970s, “Little Mo,” starring Glynis O’Connor.

Norman Brinker went on. He re-married in 1971 but that marriage was short-lived. In 1981, he met and married Nancy Goodman, who had worked as a buyer for Neiman Marcus, and then with various public relation firms. They would remain married until 2000, when they divorced, although they stayed friends and worked together in the charity that Nancy would found.

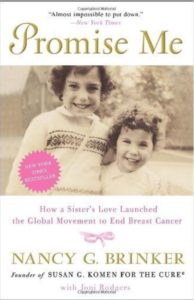

Nancy Goodman had a sister, Susan Goodman. Both were born in Peoria, Illinois. In 1976, at age 33, Susan developed breast cancer and died in August 1980, at 37-years-old. By then married and named Susan G. Komen, Nancy Brinker vowed to her sister that she would fight the disease in her memory. Using some of Norman Brinker’s fortunes from his restaurant businesses, she formed the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation in 1982. In 2008 the foundation would change its name to the Susan G. Komen Fight for the Cure.

Brinker not only founded the Susan G. Komen Foundation, but eventually served as its CEO until 2012. It has become the largest and best-funded breast cancer organization in the world.

The Susan G. Komen Foundation was not Nancy Brinker’s only accomplishment in life. In 2001 she was named Ambassador to Hungary by George W. Bush and served in that role from 2001-03. She later was US Chief of Protocol under President Bush from 2007-09, holding the title of ambassador and assistant under-secretary of state in that role. Continuing her fight against cancer, Nancy Brinker later became the World Health Organization’s Goodwill Ambassador for Cancer Control.

Norman Brinker, like his first wife, Little Mo, was badly injured in a riding accident in 1993, breaking multiple bones, residing in a coma, and ended up partially paralyzed. Still, he returned to his restaurant businesses six months later and would live until 2009. After their divorce in 2000, he and Nancy Brinker stayed close, and he remained on the board of the Susan G. Koman Foundation until his death. In his honor, the restaurant business gives out The Norman Award annually, to industry executives.

Norman Brinker – an Olympian and restaurant pioneer; Maureen Connolly – one of the greatest tennis players ever; Susan G. Komen – a breast cancer victim whose death spurred the greatest charitable breast cancer organization; and her sister, Nancy Brinker – who vowed that Susan’s death would not be in vain. A remarkable family touching so many aspects of American and world life. You should know about them.