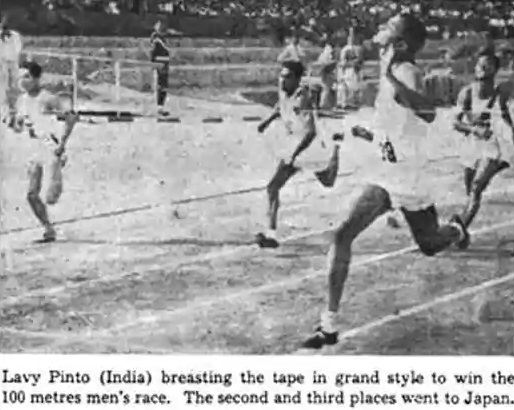

Today on the Oldest Olympians blog, we wanted to provide our readers with updates to several cases that we have discussed in the past, but have now been resolved. This inspiration for this post comes from Gulu Ezekiel, who was able to confirm that Lavy Pinto, who represented India in two track events at the 1952 Helsinki Games, and whom we profiled recently, did in fact die on February 15 at the age of 90.

These new updates come thanks to the diligent work of Connor Mah and Rob Gilmore, who were able to not only confirm the details of some of our past cases, but uncover a plethora of biographical data for many lesser-known Olympians as well (but that is, perhaps, for another blog post). In one case, they even preempted one of our long-term mysteries, that of Canadian boxer Roy Keenan. Keenan, born August 26, 1930, represented Canada in light-welterweight boxing at the 1952 Helsinki Games, where he was eliminated in the first round by Piet van Klaveren of the Netherlands. We had long known about an obituary for a Roy Keenan who died May 21, 2003 that contained insufficient identifying details, and were planning to feature him in a blog post after the 90th anniversary of his birth. Just recently, however, Mah was able to confirm that this was indeed the Olympic boxer.

One case that we have featured in the past that was solved by Mah and Gilmore was that of Jacques Carbonneau, born May 11, 1928, who represented Canada as one of the nation’s two cross-country skiers at the 1952 Oslo Olympics, where he finished 70th in the 18 km event. Through their research, they were able to confirm that an obituary in the March 15, 2007 edition of La Presse, stating that a Jacques Carbonneau, born in 1928, had died two days earlier, was in fact that of the Olympian.

Mah also pointed us in the direction of Carl Horn, son of Olympic fencer Alf Horn, who took part in five events at the 1948 London Games. As it turns out, from a communication with Carl, the Alf Horn who died in August 1978 was not the Olympian – the Olympic Alf Horn died April 5, 1991 in Montreal, which demonstrates that even when the evidence seems convincing, it is often important to get further confirmation.

Finally, a small update to one of our more popular stories, that of Canadian ski jumper Bob Lymburne, is that we were able to confirm from a relative that the story of him walking off into the woods and (presumably) dying was in fact true. While we were unable to ascertain a precise date (or even year), confirmation of the story brings us one step closer to solving that mystery. We hope that you have found these updates useful and interesting, and that you will join us again next week as we look into more Olympic mysteries!