Since it has been a few months, today on Oldest Olympians we have decided that it is time to review some of the Olympic Missing Links that have accumulated since our last post. Thus, today we are once again looking at cases for whom we believed to have identified their date of death but, for whatever reason, we were unable to connect the information, such as obituary or public record, conclusively to the athlete. As always, we present them here not only in the hopes of solving some of these cases, but to continue our commitment to transparency in our research.

(Eduardo Cordero, wearing shirt #6)

Eduardo Cordero – Member of Chile’s basketball delegation at the 1948 and 1952 Summer Olympics

Eduardo “El Mago” Cordero, born September 12, 1921, was a member of two Chilean Olympic basketball teams. In 1948 in London, the nation ranked sixth, while in 1952 in Helsinki it improved to fifth. In between, he won a bronze medal at the 1950 Basketball World Cup. Cordero was a well-known player domestically in Chile, but the only evidence of his later life that we could uncover was an anonymous edit to Wikipedia that claimed that he died in 1991 in Valparaiso. Although Chilean genealogical records have been very helpful in the past for identifying the fates of the country’s Olympic athletes, in this case they were unable to confirm the information that was added to Wikipedia.

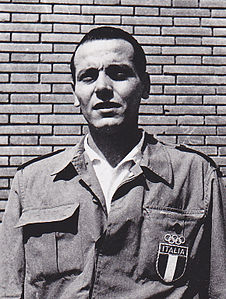

(Grave for Manuel Escobar Palomo at BillionGraves)

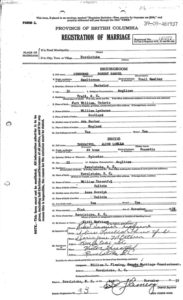

Manuel Escobar – Member of El Salvador’s sailing delegation to the 1968 Mexico City Olympics

Like many Olympic sailors, we know little about Manuel Escobar, born August 6, 1924, outside of the fact that he represented El Salvador in the Flying Dutchman class at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. Alongside Mario Aguilar (another Olympian on our “possibly living” list), he finished 30th and last. The only other potential trace we have of him is a picture of the grave of a Manuel Escobar Palomo born in 1924 who died in Guatemala in 1995. In this case, the year of birth and the full name match, but the country does not. While it certainly would be possible for the Olympian to have moved to a neighboring country (especially when one presumes that an Olympic sailor would have the resources to do so), we cannot claim with certainty that the grave is his.

Pierre William – Member of France’s athletics delegation at the 1960 Rome Olympics

Pierre William, born December 17, 1928 in Senegal, was at his athletic peaking during the early 1960s. At the turn of the decade, he represented France in the triple jump at the 1960 Rome Olympics, where he finished last and did not survive the qualifying round. Less than three weeks later, however, he set a French national record in that event with a jump of 16 metres. William then became the national triple jump champion in 1961, but faded after that. Someone who is possibly a relative posted that he died on December 21, 2018 in Dakar but, despite how recent this is said to have occurred, we were unable to verify this information.

That is it for today, but we hope that you will come back next week, when we will have more Olympic mysteries to share with you all!