Last month we noted the 104th birthday of American kayaker John Lysak, born August 16, 1914, who is, to the best of our knowledge, the oldest living Olympian. As we have mentioned in the past, however, there are approximately 2500 Olympians born between 1908 and 1928 for whom we have no confirmation on whether they are alive or deceased, not counting the 564 Olympians who participated in the Games in 1928, 1932, and 1936 for whom we have no information on their date, or even year, of birth. Today we want to focus on a small subset of those 2500, the 231 Olympians who would be older than John Lysak if they were still alive. We have already covered the two medalists who fall into this category, Ibrahim Orabi and Adolf Müller, and 16 more are either non-starters or demonstration event competitors, so to shorten the list just a little, we are going to look at the remaining 213 by year of birth.

It should be noted that discussing these individuals in no way represents any belief on the part of Oldest Olympians that these athletes are still alive; we simply cannot confirm that they are deceased. In fact, we find it highly unlikely that any Olympian who is between the age of 104 and 109 would have somehow escaped our attention completely. It remains, however, an important caveat and is always a possibility: language barriers, poor media coverage of older athletes, and desire for privacy from a generation when the Games were not as big as they are now all contribute to the chance that someone may have eluded our radar. In the past, several Olympic centenarians have reached that milestone with little public fanfare, sometimes not being revealed until their death. We therefore feel that it is important to share this list to make our research methods a little more public and subject to scrutiny, and perhaps solve a case or two along the way.

On the left, Abdel Sattar Tarabulsi, who represented Lebanon in sport shooting at the 1952 Summer Olympics. Photograph from: https://www.abdogedeon.com/volleyball/NOUJOUM/abdelsattar%20traboulsi.html

1908

[table]

Name,Nation,Sport,Birthday

Sayed Mohammad Ayub,Afghanistan,Field hockey,November 20 1908

Cecil Bissett,Zimbabwe,Boxing,1908

Abdel Sattar Tarabulsi,Lebanon,Sport shooting,1908

Elfriede Zimmermann,Germany,Swimming,1908

[/table]

Syed Muhammad Salim, who represented Pakistan in field hockey at the 1948 Summer Olympics

1909

[table]

Name,Nation,Sport,Birthday

Abdullah Jaroudi Sr.,Lebanon,Sport shooting, 1909

Ahmed Ibrahim Kamel,Egypt,Diving,1909

Khalil Ibrahim,Egypt,Diving,1909

Yuki Mawatari,Japan,Swimming,1909

Tetsutaro Namae,Japan,Diving,1909

Syed Muhammad Salim,Pakistan,Hockey,September 5 1909

Rokuro Takahashi,Japan,Rowing,1909

[/table]

Rashad Shafshak, who was a member of Egypt’s 1936 Olympic basketball team

1910

[table]

Name,Nation,Sport,Birthday

Henrique Camargo,Brazil,Rowing,October 28 1910

Paul Cerutti,Monaco,Sport shooting,November 30 1910

Alberto Conrad,Bolivia,Swimming,March 26 1910

Hoo Kam Chiu,Hong Kong,Sport shooting,May 7 1910

Rafael Lang,Argentina,Boxing,September 5 1910

Eduardo Lehman,Brazil,Rowing,April 28 1910

José López,Argentina,Cycling,1910

Heitor Medina,Brazil,Athletics,July 10 1910

Floyd Morgenstern,United States,Art competitions,June 25 1910

Hércules Morini,Argentina,Sailing,May 17 1910

Cid Nascimento,Brazil,Sailing,November 23 1910

Tabaré Quintans,Uruguay,Basketball,May 9 1910

Ricardo Rey,Argentina,Wrestling,1910

José Rodríguez,Argentina,Fencing,March 19 1910

Eduardo Sastre,Argentina,Fencing,September 22 1910

Rashad Shafshak,Egypt,Basketball,November 26 1910

Zahir Shah Al-Zadah,Afghanistan,Hockey,November 18 1910

Irina Timcic,Romania,Figure skating,September 4 1910

Eduardo Vargas,Argentina,Boxing,February 26 1910

[/table]

Dora Schönemann competed in two swimming events for Germany at the 1928 Summer Olympics

1911

[table]

Name,Nation,Sport,Birthday

August Banščak,Yugoslavia,Athletics,October 10 1911

Tomás Beswick,Argentina,Athletics,October 17 1911

Juan Bregaliano,Uruguay,Boxing,November 22 1911

José Castillo,Cuba,Diving,March 6 1911

João Francisco de Castro,Brazil,Rowing,December 12 1911

Rui Duarte,Brazil,Modern pentathlon,July 30 1911

Mohamed Ebeid,Egypt,Athletics,April 11 1911

Maximo Fava,Brazil,Rowing,August 12 1911

Margarethe Held,Austria,Athletics,March 19 1911

Julio Herrera,Mexico,Equestrian,March 16 1911

Flora Hofman,Yugoslavia,Athletics,November 17 1911

Hassan Ali Imam,Egypt,Wrestling,August 12 1911

Shigetaka Katsuhisa,Japan,Water polo,September 4 1911

Carlos Kennedy,Argentina,Swimming,February 16 1911

Mohammad Khan,Afghanistan,Athletics and field hockey,May 1 1911

Makoto Kikuchi,Japan,Field hockey,1911

Seibei Kimura,Japan,Water polo,October 11 1911

Hector de Lima Polanco,Venezuela,Sport shooting,March 25 1911

Vasile Moldovan,Romania,Gymnastics,August 28 1911

Horacio Monti,Argentina,Sailing,August 12 1911

Grete Nissl,Austria,Alpine skiing,November 30 1911

Ibrahim Okasha,Egypt,Athletics,1911

Ennio de Oliveira,Brazil,Fencing,November 5 1911

Mario Ortíz,Argentina,Sailing,November 21 1911

Jorge Patiño,Peru,Sport shooting,December 18 1911

Juan Paz,Peru,Swimming,September 16 1911

Olivério Popovitch,Brazil,Rowing,October 1911

Domingos Puglisi,Brazil,Athletics,November 4 1911

Ruben Ribeiro,Brazil,Equestrian,May 25 1911

Lukman Saketi,Indonesia,Sport shooting,1911

José Domingo Sánchez,Colombia,Athletics,May 20 1911

Álvaro dos Santos Filho,Brazil,Sport shooting,October 22 1911

Luis Sardella,Argentina,Boxing,July 11 1911

Irmintraut Schneider,Germany,Swimming,1911

Dora Schönemann,Germany,Swimming,1911

Fumio Takashina,Japan,Diving,1911

Humberto Terzano,Argentina,Equestrian,1911

Pedro Theberge,Brazil,Water polo,January 1911

[/table]

Roma Wagner represented Austria as a 100 metre swimmer at the 1936 Summer Olympics

1912

[table]

Name,Nation,Sport,Birthday

Antonio Adipe,Uruguay,Boxing,April 24 1912

Luis Albornoz,Peru,Sport shooting,November 18 1912

Baiano,Brazil,Basketball,September 27 1912

Alberto Batignani,Uruguay,Waterpolo,September 30 1912

Humberto Bernasconi,Uruguay,Basketball,November 17 1912

Carlos Choque,Argentina,Sport shooting,August 22 1912

Francisco Costanzo,Uruguay,Boxing,November 4 1912

Marcel Couttet,France,Ice hockey,April 27 1912

Iosif Covaci,Romania,Alpine and cross-country skiing,December 2 1912

Constantin David,Romania,Boxing,December 25 1912

José Feans, Uruguay,Boxing,April 24 1912

João de Faria,Brazil,Sport shooting,August 31 1912

Kenichi Furuya,Japan,Ice hockey,November 8 1912

Sergio Iesi,Uruguay,Fencing,April 8 1912

Luis Jacob,Peru,Basketball,August 13 1912

Julio Juaneda,Argnetina,Weightlifting,1912

Kozue Kinoshita,Japan,Ice hockey,April 15 1912

Osamu Kitamura,Japan,Rowing,June 29 1912

Theo Kitt,Germany,Bobsledding,October 14 1912

Ovidio Lagos,Argentina,Sailing,July 21 1912

Robert Landesmann,France,Wrestling,March 26 1912

Miguel Lopes,Brazil,Basketball,July 6 1912

Mario de Lorenzo,Brazil,Water polo,July 1912

Shoichi Masutomi,Japan,Wrestling,January 12 1912

René Morel,France,Athletics,February 21 1912

Tadashi Murakami,Japan,Athletics,October 7 1912

Marcel Noual,France,Swimming,1912

Toshio Ohtsu,Japan,Field hockey,January 23 1912

Celestino João de Palma,Brazil,Rowing,December 21 1912

Rigoberto Pérez,Mexico,Athletics,November 26 1912

Hilda von Puttkammer,Brazil,Fencing,August 13 1912

Constantin Radu,Romania,Athletics,February 13 1912

Roy Ramsay,Bahamas,Sailing,September 28 1912

Jean-Albin Régis,France,Sport shooting,February 19 1912

Kamal Riad Noseir,Egypt,Basketball,January 8 1912

Anísio da Rocha,Brazil,Modern pentathlon and equestrian,October 13 1912

José Manuel Sagasta,Argentina,Equestrian,1912

Tadashi Shimijima,Japan,Rowing,October 8 1912

Guillermo Suárez,Peru,Athletics,September 8 1912

Shoichiro Takenaka,Japan,Athletics,September 30 1912

Kojiro Tamba,Japan,Wrestling,May 10 1912

Noboru Tanaka,Japan,Field hockey,1912

Rogério Tavares,Portugual,Sport shooting,December 3 1912

Taro Teshima,Japan,Rowing,July 14 1912

Kenshi Togami,Japan,Athletics,August 1 1912

Pedro del Vecchio,Colombia,Athletics,October 16 1912

Sigfrido Vogel,Argentina,Sport shooting,September 1912

Roma Wagner,Austria,Swimming,July 21 1912

[/table]

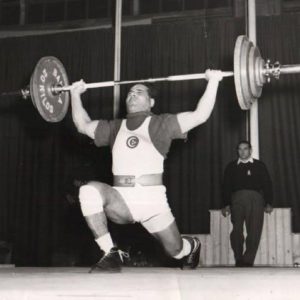

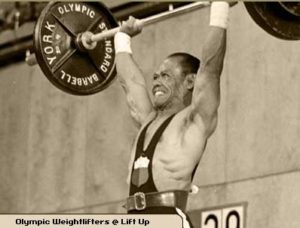

Pedro Landero, who represented Philippines in bantamweight weightlifting at the 1952 and 1956 Summer Olympics. Photograph from: http://www.chidlovski.net/liftup/l_athleteStatsResult.asp?a_id=1902

1913

[table]

Name,Nation,Sport,Birthday

Osamu Abe,Japan,Rowing,August 11 1913

Mohamed Amin,Egypt,Boxing,November 15 1913

Willy Angst,Switzerland,Wrestling,November 20 1913

Sayed Ali Atta,Afghanistan,Field hockey,August 25 1913

Frédéric Boeni,Switzerland,Diving,November 15 1913

Louis Chauvot,France,Sailing,February 14 1913

Georges Conan,France,Cycling,1913

Pierre Cousin,France,Athletics,June 14 1913

Frederic Drăghici,Romania,Gymnastics,June 1 1913

Juan Andrés Dutra,Uruguay,Rowing,October 10 1913

Mahmoud Ezzat,Egypt,Boxing,September 11 1913

Georges Firmenich,Switzerland,Sailing,December 3 1913

Ernst Fuhrimann,Switzerland,Cycling, June 28 1913

Werner George,Germany,Ice hockey,September 12 1913

Juan de Giacomi,Argentina,Sport shooting, 1913

Oscar Goulú,Argentina,Equestrian, 1913

Mario Guerci,Argentina,Rowing,January 14 1913

Tsugio Hasegawa,Japan,Figure skating, June 18 1913

Mohamed Hassanein,Egypt,Swimming,1913

Ludovic Heraud,France,Sport shooting,January 1 1913

Masao Ichihara,Japan,Athletics,November 7 1913

Albino de Jesus,Portugal,Sport shooting,August 13 1913

Koichi Kawaguchi,Japan,Equestrian,March 12 1913

Ludovico Kempter,Argentina,Sailing,November 11 1913

Werner Klingelfuss,Switzerland,Canoeing,June 11 1913

Alfred König,Austria,Athletics,October 2 1913

Hiroyoshi Kubota,Japan,Athletics,April 29 1913

Daiji Kurauchi,Japan,Field hockey,1913

Pedro Landero,Philippines,Weightlifting,October 19 1913

Melchor López,Argentina,Sport shooting,January 7 1913

Florio Martel,France,Field hockey,March 2 1913

Jaime Mendes,Portugal,Athletics,August 20 1913

Fernand Mermoud,France,Cross-country skiing,August 20 1913

Isamu Mita,Japan,Rowing,March 25 1913

Yoshio Miyake,Japan,Gymnastics,December 7 1913

Severino Moreira,Brazil,Sport shooting,September 29 1913

Zafar Ahmed Muhammad,Pakistan,Sport shooting,July 10 1913

Mie Muraoka,Japan,Athletics,March 23 1913

Takao Nakae,Japan,Basketball,April 30 1913

Chiyoto Nakano,Japan,Boxing,February 7 1913

Yoshio Nanbu,Japan,Weightlifting,March 22 1913

Karl Neumeister,Austria,Equestrian,August 15 1913

Jwani Riad Noseir,Egypt,Basketball,February 6 1913

Wanda Nowak,Austria,Athletics,January 16 1913

Benvenuto Nuñes,Brazil,Swimming,June 27 1913

Edmund Pader,Austria,Swimming,1913

Dumitru Panaitescu,Romania,Boxing,May 1 1913

Prudencio de Pena,Uruguay,Basketball,January 21 1913

Dumitru Peteu,Romania,Bobsledding,October 19 1913

Abdul Rahim,Afghanistan,Athletics,February 11 1913

Olga Rajkovič,Yugoslavia,Athletics,April 13 1913

Hertha Rosmini,Austria,Alpine skiing,November 9 1913

Shusui Sekigawa,Japan,Rowing,May 13 1913

Chikara Shirasaka,Japan,Rowing,August 18 1913

Jelica Stanojević,Yugoslavia,Athletics,July 1 1913

José de la Torre,Mexico,Sport shooting,April 3 1913

Pierre Vandame,France,Field hockey,June 17 1913

Anton Vogel,Austria,Wrestling,July 21 1913

[/table]

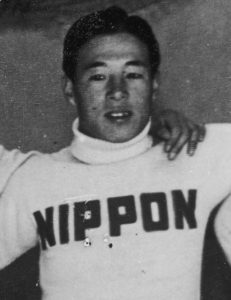

Yushoku Cho, who represented Japan in two speed skating events at the 1936 Winter Olympics.

1914

[table]

Name,Nation,Sport,Birthday

Toyoyi Aihara,Japan,Athletics,January 7 1914

Ion Baboe,Romania,Athletics,April 12 1914

Charles Campbell,Canada,Rowing,July 2 1914

José Cazorla,Venezuela,Sport shooting,February 26 1914

Yushoku Cho,Japan,Speed skating,January 18 1914

Werner Christen,Switzerland,Athletics,April 29 1914

Asa Dogura,Japan,Athletics,June 11 1914

Jean Fournier,France,Sport shooting,May 4 1914

Hugo García,Uruguay,Water polo,March 20 1914

Mitsue Ishizu,Japan,Athletics,April 16 1914

Josef Jelen,Czechoslovakia,Boxing,August 10 1914

Thea Kellner,Romania,Fencing,March 6 1914

Grete Lainer,Austria,Figure skating,June 20 1914

František Leikert,Czechoslovakia,Canoeing,May 6 1914

Masayasu Maeda,Japan,Basketball,March 10 1914

Khalil Amira El-Maghrabi,Egypt,Boxing,January 1 1914

Gheorghe Man,Romania,Fencing,March 20 1914

Georges Meyer,Switzerland,Athletics,April 17 1914

Hans Mohr,Yugoslavia,Athletics,August 6 1914

Karl Molnar,Austria,Canoeing,May 18 1914

Isaac Moraes,Brazil,Swimming,July 26 1914

František Mráček,Czechoslovakia,Wrestling,April 13 1914

Fausto Preysler,Philippines,Sailing,February 14 1914

Rosalvo Ramos,Brazil,Athletics,June 6 1914

Roger Rouge,Switzerland,Sailing,June 1 1914

Julio César Sagasta,Argentina,Equestrian,July 13 1914

Antônio Luiz dos Santos,Brazil,Swimming,July 16 1914

František Šír,Czechoslovakia,Rowing,January 22 1914

Noboru Sugimoto,Japan,Swimming,April 6 1914

Kosei Tano,Japan,Water polo,January 22 1914

Paulo Tarrto,Brazil,Swimming,April 12 1914

Anwar Tawfik,Egypt,Fencing,July 31 1914

Annie Villiger,Switzerland,Diving and swimming,April 4 1914

Takimi Wakayama,Japan,Water polo,March 30 1914

Zenjiro Watanabe,Japan,Figure skating,February 11 1914

Georg Weidner,Austria,Wrestling,January 14 1914

Otto Weiß,Germany,Figure skating,April 20 1914

Dragana Đorđević,Yugoslavia,Gymnastics,June 2 1914

[/table]

Having produced this table, we may in the future decide to create a more detailed and sortable table, including Olympic participations, on our website (which is here by the way) so that we can update it as time goes on. Next week, however, we will take a look at those 16 non-starters and demonstration event competitors in order to complete our look into the realm of research on the Oldest Olympians. We hope you will join us!