It was announced on Wednesday that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and NBC, the United States television network that has televised the Summer Olympics since 1988, have signed an agreement extending NBC’s hegemony over the Summer Olympics in the United States through 2032. The fee was $7.65 billion (US) – that’s billion, which sounds like a huge amount of Franklins – for the rights to the Summer and Winter Games from 2022-2032. We’ll disregard the $100,000,000 signing bonus, presumably for the IOC signing their name nicely, which technically makes it $7.75 billion. How does this compare to previous Olympic television rights in the United States and how have they increased over time?

The Olympic Games have been televised in the United States since 1960. In 1960 CBS Television paid Rome $394,940 for the rights fee, and CBS also paid Squaw Valley $50,000 for the rights fee. Looks like those fees have really skyrocketed over the years, and it continues to skyrocket. As we always do, let’s look at the numbers.

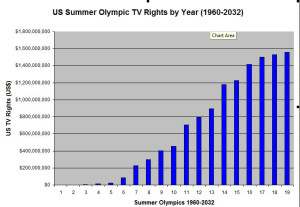

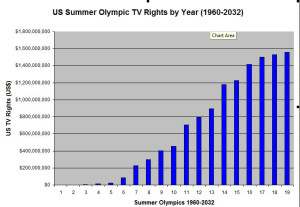

Below are all the Summer Olympics since 1960, with the host city, the US network televising them, and the rights fee. In the far right column, we have calculated the change in rights fees (ΔRF) since 1960. As you can see the US television rights for the Summer Olympics have gone up almost 400000% since 1960. Now we made a few assumptions for 2024-2032. It is known that the rights for 2022/2024, 2026/2028, and 2030/2032 are divvied up as $2.50B, $2.55B, and $2.60B. It isn’t yet known how much of that is allocated to the Summer Olympics and how much to the Winter Olympics. We arbitrarily allocated 60% of each period to the Summer Olympics and 40% to the Winter Olympics, which is approximately the historical average.

[table]

Year,Host,Network,Rights Fee,ΔRF

1960,Rome,CBS,$394940,—

1964,Tokyo,NBC,$1500000,380%

1968,Mexico City,ABC,$4500000,1139%

1972,Munich,ABC,$13500000,3418%

1976,Montréal,ABC,$25000000,6330%

1980,Mockba,NBC,$85000000,21522%

1984,Los Angeles,ABC,$225600000,57123%

1988,Seoul,NBC,$300000000,75961%

1992,Barcelona,NBC,$401000000,101534%

1996,Atlanta,NBC,$456000000,115461%

2000,Sydney,NBC,$705000000,178508%

2004,Athens,NBC,$793500000,200917%

2008,Beijing,NBC,$893000000,226110%

2012,London,NBC,$1181000000,299033%

2016,Rio de Janeiro,NBC,$1226000000,310427%

2020,Tokyo,NBC,$1418000000,359042%

2024,TBD,NBC,$1500000000,379805%

2028,TBD,NBC,$1530000000,387401%

2032,TBD,NBC,$1560000000,394997%

[/table]

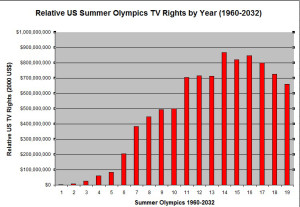

This is what the chart of those increases looks like, showing the huge upward trend although it does seem to taper off a bit at the right-hand side of the chart.

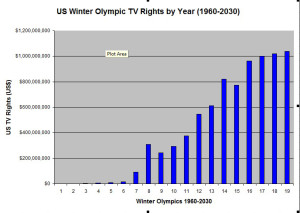

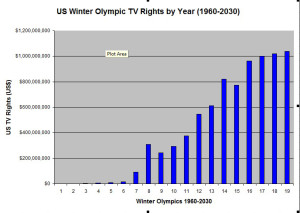

Here are the corresponding numbers for the US television rights for the Winter Olympics. The original fee of $50,000 for Squaw Valley will increase to $1,040,000,000 for the 2030 Winter Olympics, wherever they may be held. This is an absolute increase even greater than for the Summer Olympics, checking in at just over a 2000000% (that’s 2 million percent) increase, mainly due to the pittance paid for the 1960 rights.

[table]

Year,Host,Network,Rights Fee,ΔRF

1960,Squaw Valley,CBS,$50000,—

1964,Innsbruck,ABC,$597326,1195%

1968,Grenoble,ABC,$2000000,4000%

1972,Sapporo,NBC,$6401000,12802%

1976,Innsbruck,ABC,$10000000,20000%

1980,Lake Placid,ABC,$15500000,31000%

1984,Sarajevo,ABC,$91550000,183100%

1988,Calgary,ABC,$309000000,618000%

1992,Albertville,CBS,$243000000,486000%

1994,Lillehammer,CBS,$295000000,590000%

1998,Nagano,CBS,$375000000,750000%

2002,Salt Lake City,NBC,$545000000,1090000%

2006,Torino,NBC,$613400000,1226800%

2010,Vancouver,NBC,$820000000,1640000%

2014,Sochi,NBC,$775000000,1550000%

2018,Pyeongchang,NBC,$963000000,1926000%

2022,TBD,NBC,$1000000000,2000000%

2026,TBD,NBC,$1020000000,2040000%

2030,TBD,NBC,$1040000000,2080000%

[/table]

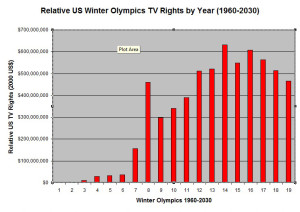

Here’s what the chart of the Winter Olympics rights increases look like since 1960, again showing some flattening at the right-hand side, near 2022-2030.

So it looks like the US television networks, and since 1988, that pretty much means NBC, are paying out the wazoo for the Olympics, and possibly severely overpaying. But are they really? NBC announced very good ratings for the recent Sochi Olympics and announced that they were pleased with their return on investment (ROI).

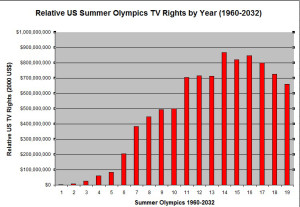

How about if we look at the numbers for rights fees corrected against inflation? In 1960, a hamburger at McDonald’s, an Olympic sponsor since 1997, cost 25¢, while today the same hamburger costs you around $1.00. So based on that it appears that the US dollar has inflated about 4 times since 1960. But that only reflects the cost of a McDonald’s hamburger. The actual historical figures in the United States have the US dollar inflated about 8 times since 1960.

Now we have to make some assumptions to analyze this thru 2032, since we don’t know what inflation will be from 2014-2032. In our analysis below, we used an annual inflation rate of 2.81% in the US for 2014-2032, because that has been the annual inflation rate from 1988-2013, or the period when NBC really became the US Olympic Network.

So here is what the numbers look like, corrected against inflation. In the following we have used the benchmark as the value of the US dollar in 2000, a nice benchmark year as the end of the millennium.

[table]

Year,Host,Network,RRF,ΔARF,ΔRRF

1960,Rome,CBS,$2541996,—,—

1964,Tokyo,NBC,$9180704,361%,361.2%

1968,Mexico City,ABC,$25168221,990%,274.1%

1972,Munich,ABC,$61622693,2424%,244.8%

1976,Montréal,ABC,$83826050,3298%,136.0%

1980,Mockba,NBC,$205738715,8094%,245.4%

1984,Los Angeles,ABC,$384700667,15134%,187.0%

1988,Seoul,NBC,$446313591,17558%,116.0%

1992,Barcelona,NBC,$493600318,19418%,110.6%

1996,Atlanta,NBC,$499993768,19669%,101.3%

2000,Sydney,NBC,$705000000,27734%,141.0%

2004,Athens,NBC,$716275315,28178%,101.6%

2008,Beijing,NBC,$712879459,28044%,99.5%

2012,London,NBC,$867348798,34121%,121.7%

2016,Rio de Janeiro,NBC,$820155950,32264%,94.6%

2020,Tokyo,NBC,$846386112,33296%,103.2%

2024,TBD,NBC,$798858546,31426%,94.4%

2028,TBD,NBC,$727036786,28601%,91.0%

2032,TBD,NBC,$661417806,26020%,91.0%

[/table]

RRF = relative rights fee, ΔARRF = change in absolute relative rights fees (since 1960), ΔRRF = change in relative rights fees Olympics-to-Olympics

You can see that corrected against inflation, the rise in US television rights fees is not so dramatic, going up not 400K% since 1960, but about 26K%. Still a huge increase, but looking at it more closely, from 2000-2032 there will be very little change in the relative rights fees NBC is paying, corrected for inflation. In fact, from 2012-2032 the relative rights fees paid to the IOC will mostly decrease, except for a small upward blip for Tokyo in 2020. Here is what the chart looks like, which shows the downward trend starting after London (14 below).

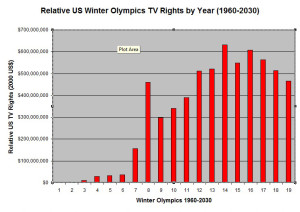

Here are the similar figures for the Winter Olympics, again corrected against inflation from 1960-2030, using the same assumption about rates 2014-2030, and using the 2000 US dollar as the benchmark. Again note that the fees do not go up 2 million percent, but about 145000% – still a huge increase. But now starting in 2002, from Salt Lake City onward, there is not much change in relative US television rights fees. Again, after Vancouver in 2010 the trend is mostly downward, except for another small upward blip for Pyeongchang in 2018.

[table]

Year,Host,Network,RRF,ΔARF,ΔRRF

1960,Squaw Valley,CBS,$321820,—,—

1964,Innsbruck,ABC,$3655916,1136%,1136.0%

1968,Grenoble,ABC,$11185876,3476%,306.0%

1972,Sapporo,NBC,$29218286,9079%,261.2%

1976,Innsbruck,ABC,$33530420,10419%,114.8%

1980,Lake Placid,ABC,$37517060,11658%,111.9%

1984,Sarajevo,ABC,$156114123,48510%,416.1%

1988,Calgary,ABC,$459702999,142845%,294.5%

1992,Albertville,CBS,$299114407,92944%,65.1%

1994,Lillehammer,CBS,$341661893,106165%,114.2%

1998,Nagano,CBS,$389670308,121083%,114.1%

2002,Salt Lake City,NBC,$511728840,159011%,131.3%

2006,Torino,NBC,$520435355,161716%,101.7%

2010,Vancouver,NBC,$632247732,196460%,121.5%

2014,Sochi,NBC,$548863699,170550%,86.8%

2018,Pyeongchang,NBC,$608520791,189087%,110.9%

2022,TBD,NBC,$563813489,175195%,92.7%

2026,TBD,NBC,$513123568,159444%,91.0%

2030,TBD,NBC,$466811406,145053%,91.0%

[/table]

Here is the chart for the relative Winter Olympics rights fees, demonstrating the downward trend in the last few years of the NBC contracts. This shows that the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City and the 2006 Winter Games in Torino (12/13 below) rights fees will be worth more than the 2030 Winter Olympics, and about the same as the 2026 Winter Olympics, in 2000 US dollars.

So it looked like a huge number – $7.65 billion – and it is, of course, in absolute dollars. But looking at it more carefully, correcting the time course corrections that will certainly occur in the US dollar, NBC may have gotten a bargain.

However, the IOC also guaranteed itself money thru 2032, ensuring a major source of its income, and it did so at rates approximately keeping pace with expected inflation. So this could certainly be a win-win deal for both parties.