Today on Oldest Olympians we wanted to wrap up 2022 by looking at some of the Olympic mysteries that we came across near the end of that year. These are individuals for whom we believe to have information about their deaths, but we either cannot connect it to the Olympian or we cannot confirm it in a reliable source.

Rudolf Procházka – Art competitor for Czechoslovakia at the 1936 Berlin Olympics

At the 1936 Berlin Olympics, a group of four architects from Czechoslovakia – Hans Ruda, Rudolf Procházka, Karel Martínek, and Egon Plefka – submitted an entry to the architecture competition entitled “Návrhem stadionu v Brně”, which was an urban study of a central sports facility for Greater Brno. It did not win a prize, and we know essentially nothing of the four architects who submitted it. We did find the grave of a Rudolf Procházka, born September 6, 1890 and died June 15, 1972, who is buried in Brno, but we cannot confirm that this is the Olympian.

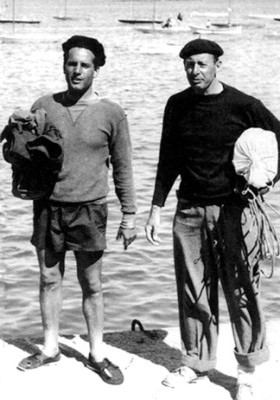

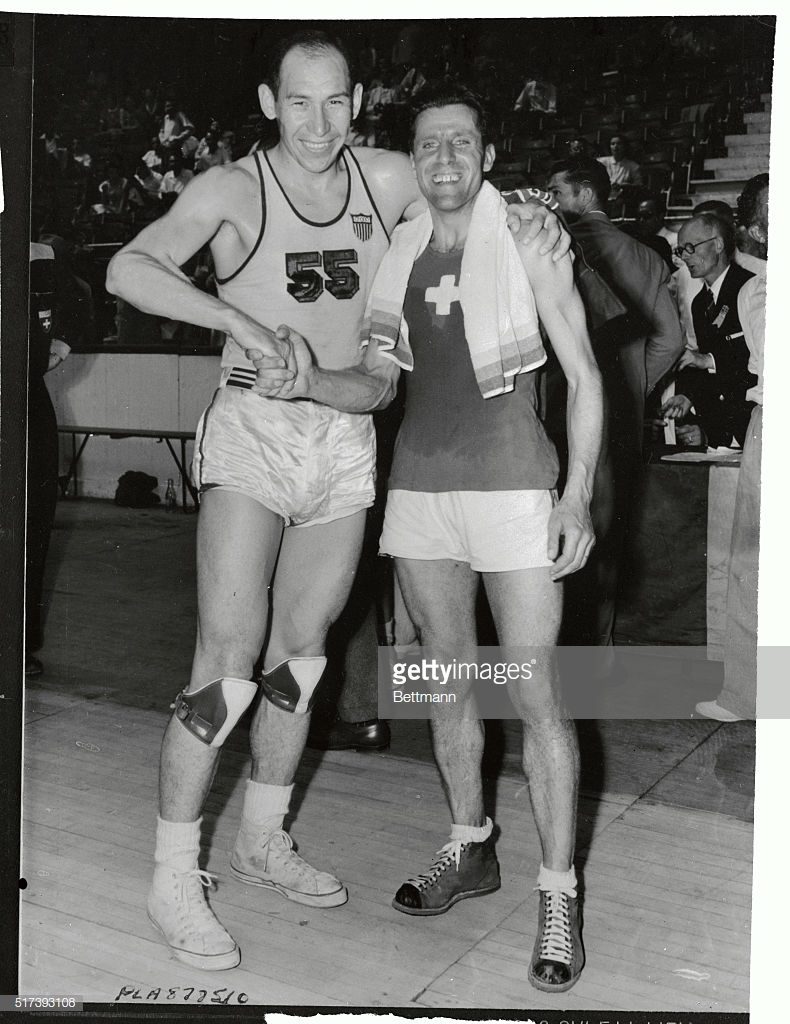

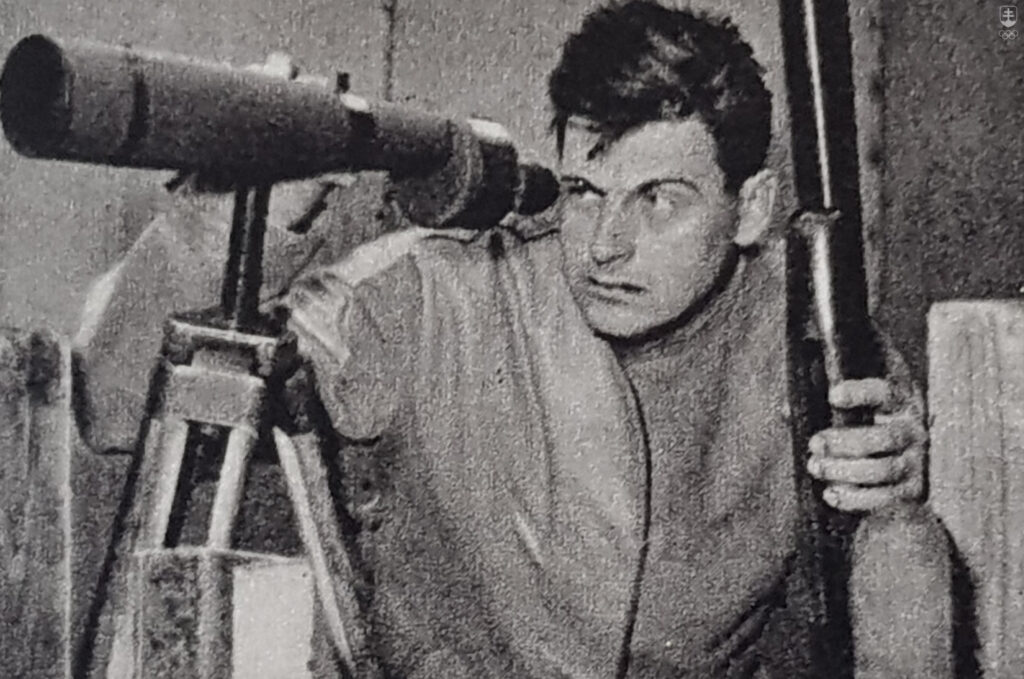

(Dušan Houdek, pictured at the Slovakian Olympic Committee)

Dušan Houdek – Member of Czechoslovakia’s sport shooting delegation to the 1960 Rome Olympics

Dušan Houdek, born April 2, 1931, represented Czechoslovakia in two small-bore rifle sport shooting events at the 1960 Rome Games. In the prone, 50 metres, competition, he was eliminated in the qualifying round, while in the three positions, 50 metres, he just missed the podium in fourth. We know that he was alive at his 90th birthday, but someone added a date of death of October 27, 2022 and a place of death of Nezdenice, Czech Republic to his Wikipedia. We have not, however, been able to confirm this.

(Dimitrios Michail, pictured at Gbotinis)

Dimitrios Michail – Member of Greece’s boxing delegation to the 1960 Rome Olympics

Dimitrios Michail, born March 19, 1932, represented Greece in the light-welterweight boxing tournament at the 1960 Rome Games, where he was eliminated in round two. He had had better luck the previous year, where he took bronze as a welterweight at the Mediterranean Games. We know that he was still alive in 2021 and living in Australia, but we are uncertain if this obituary for a Demetrios Michael, who died in July 2022, is for the Olympian.

Věra Drazdíková – Member of Czechoslovakia’s gymnastics team at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics

Věra Drazdíková, born February 1, 1933, represented Czechoslovakia in the gymnastics tournament at the 1956 Melbourne Games, where the nation was fifth in the team all-around and seventh in the team portable apparatus. Individually, Drazdíková’s best finish was 28th on the balance beam. There is a grave in Prague for a Věra Drazdíková born in 1933 who died in 1983, but we cannot confirm that it is for the Olympian.

One additional Olympic mystery concerns Hermann Lochbühler, who was a member of the German military ski patrol team that placed fifth in the demonstration event at the 1936 Garmisch-Partenkirchen Olympics. We found a record for an individual of this name who was born December 21, 1900, but we are not certain if it is for the Olympian. Finally, we wanted to provide a few updates to our posts on Olympians last known living in 2012. Thanks to our readers, we now know that Benny Schmidt was still alive in at least 2014, Milica Rožman in at least 2016, and Daphne Wilkinson as recently as 2021. Thank you to everyone who submitted information!